Cancer, Polio & Immunotherapy

June 25, 2016 | Author: Susan Silberstein, PhD

I recently wrote about intensified research interest in cancer immunotherapy spearheaded by the new Parker Institute. In a similar vein, just over a year ago, in March of 2015, CBS-Evening News anchor Scott Pelley hosted an amazing 60 Minutes show called “Killing Cancer.” I fully agree with Pelley’s assessment that “the long war on cancer has left us well short of victory. Radiation flashed on in the 19th century, chemotherapy began to drip in the 20th but, for so many, 100 years of research adds up to just a few more months of life.” Now, in the 21st century, it appears that immunotherapy may well be the game-changer, and one of the most creative and promising immune treatments comes from a very unlikely source.

For several years, scientists at Duke University have been working on an experimental immunotherapy for patients with a vicious brain cancer called glioblastoma, considered by most to be a death sentence. But Duke researchers have been successfully treating this cancer by infecting the tumors with polio – ironically, the virus that has crippled and killed for centuries and which scientists fought so hard to eradicate!

The 60 Minutes show featured the stories of three patients with aggressive glioblastoma:

- Dr. Fritz Andersen, a retired cardiologist, was diagnosed at age 70 with a large brain tumor. Expecting to be one of the 12,000 Americans killed by glioblastoma each year, he wrote his own obituary before he enrolled in the Duke trial. Three years later, he’s considered cancer-free.

- 58-year-old Nancy Justice was diagnosed with glioblastoma in 2012. Surgery, chemotherapy and radiation bought her two and a half years, but the tumor recurred and doctors gave her seven months to live. She is now fully recovered.

- In 2011, 20-year-old nursing student Stephanie Lipscomb was diagnosed with a tennis-ball sized glioblastoma. Ninety-eight percent of the tumor was removed, followed by radiation and chemotherapy. Then in 2012, the cancer returned, and she was not expected to see her 22nd birthday. Three years later, she has graduated nursing school and is disease-free.

The interviews also included conversations with Duke’s polio dream team: Dr. Darell Bigner, Director of Duke’s Brain Tumor Center; Dr. Henry Friedman, Deputy Director of the Center; Dr. John Sampson, Duke’s Chief of Neurosurgery; neuro-oncologist Dr. Annick Desjardins; and Dr. Matthias Gromeier, a molecular biologist who has been working on this therapy for 25 years.

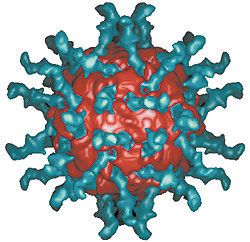

The polio virus was Dr. Gromeier’s choice because it seeks out and attaches to a receptor found on the surface of the cells that make up nearly every kind of solid tumor. By removing a key genetic sequence, Gromeier re-engineered the virus, which can no longer cause paralysis or death because it can’t reproduce in normal cells — only in cancer cells. In the process of replicating, it releases toxins that poison the cell. In 2011, after seven years of animal safety studies, the FDA approved human trials.

You may ask, why didn’t the immune system react to the cancer to begin with? As Dr. Gromeier explained, human cancers can develop a protective shield that makes them invisible to the immune system. By infecting the tumor with the virus, researchers are actually removing this protective shield, enabling cells of the immune system to enter and attack. In essence, the polio infection sets off an alarm for the immune system, signaling it to come in and kill it, and it kills the tumor in the process.

The Goal of the Clinical Trial

Clinical trials are conducted in different phases. This was a Phase 1 trial, the goal of which was simply to discover the right dose of the virus. In fact, the impressive outcomes were actually surprising, explained Dr. Friedman, “because you never expect in a Phase 1 study to have these kinds of results. You’re not expecting to cure people…You’re not even necessarily expecting to help them. You hope so. But that’s not the design of a Phase 1 study. It’s designed to get the right dose. When you get anything on top of that it’s cake.”

The plan of this experiment was to increase the dose in succeeding patients, step by step, in search of the best result. At small doses, the first two patients saw their tumors melt away, so for the next patients, the researchers increased the potency of the virus. Unfortunately, in those patients for whom the polio infusion was three times more potent than the original one, the higher dose caused an immune response that was much too powerful, the ensuing ferocious inflammation put too much pressure on the brain, treatment failed, and death ensued.

And that was the turning point in the polio trial. After experiencing failure at the higher dose, oncologist Dr. Annick Desjardins cut the potency of the infusion by 85 percent — a lower dose than they had ever intended to use in the study – and the results were much improved.

Most oncologists believe in the philosophy that if some is good, more is better. Friedman figured “if we were getting a good response at dose level one or dose level two, then go to dose level three, four, five.” That is not how I think, and although I am not a clinician, for patients undergoing chemotherapy– and even immunotherapy — I have always been a proponent of administering the lowest effective dose, as opposed to the highest tolerable dose.

Conclusion

Over a year ago, at the time the show was filmed, there were 22 patients in the polio trial. Half died, most on the higher dose — although they lived months longer than expected. The other 11 continued to improve, with an increase in median survival of over six months – which, sadly, is considered huge in glioblastoma — and by March of 2015 some patients were stable 34 months out. Typically that is unheard of in conventional arenas for this disease, which, left untreated, is expected to double in size every few weeks. Study director Dr. Bigner, who has been fighting brain cancers for 50 years, stated he has never seen results like those.

Dr. Gromeier and his team have also been testing polio immunotherapy against a number of other cancers in vitro (in a laboratory dish), including cancers of the lung, breast, colon, prostate, pancreas, liver and kidney. According to the scientists, some of the results in these early experiments appear nearly miraculous.

Such research offers promise that immunotherapy will soon join surgery, chemotherapy and radiation as a fourth mainstream weapon against cancer. My hope is that it will actually surpass the immunosuppressive therapies by encouraging a paradigm shift in how we go about treating cancer.

For More Information: For more information on clinical trials for newly diagnosed glioblastoma or recurrent glioblastoma at Duke University, call (919) 684-5301 or copy and paste this URL in your browser: http://www.cancer.duke.edu/btc/modules/ClinicalTrials4/index.php?id=111

Join the conversation: Ask Holistic Cancer Coach Facebook Group

References:

[1] http://www.cancer.duke.edu/btc/modules/ClinicalTrials4/index.php?id=2

[2] http://www.cbsnews.com/news/polio-cancer-treatment-duke-university-60-minutes-scott-pelley/, March 29, 2015