The Legacy of Jackie Kennedy

July 28, 2017 | Author: Diane Perlman, PhD

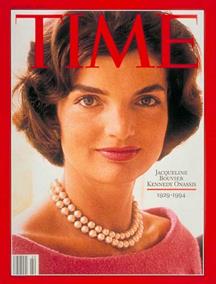

[Editor’s Note: Today, July 28, would have been Jackie Kennedy Onassis’ 88th birthday. In actuality, the widow of our assassinated President John F. Kennedy died of lymphatic cancer in 1994 at the age of 64. That year, I published in our newsletter an article by Dr. Diane Perlman entitled “The Legacy of Jackie Kennedy.” I reproduce that here, followed by Dr. Perlman’s updated reflections relevant to the expression of grief].

On the evening of May 18, 1994, as Jackie Kennedy Onassis lay on her deathbed, I was speaking to a group of people with cancer, their loved ones, and health care professionals about the psychological, emotional, and relational aspects of cancer and recovery, as a part of a seminar entitled “Maximizing Your Healing Potential” sponsored by the Center for Advancement in Cancer Education.

I often speak about cancer as a disease of civilization, referring not only to the effect on our natural environment, but also to the consequences of the civilization of our emotions. For years I have used the image of Jackie Kennedy’s composure at her husband’s funeral as a symbol of our culture’s valorization of suppressing the expression of a most natural emotion. To an audience of vigorously nodding heads, I describe how as an adolescent in 1963, I couldn’t understand why Jackie wasn’t crying. I found it even more difficult to fathom why everybody thought that that was so wonderful. My comments here are not about Jackie as a person, but about Jackie as a symbol. Actually these comments are about us, about our culture and our need to cling to a symbol of composure.

Scientists have now accumulated a respectable body of research on the relationship between the emotions and immune function. Personality factors such as stoicism, conflict avoidance, and being too well-adjusted are all associated with immune suppression on measures such as reduced number and activity of natural killer cells that destroy cancer cells. Self-reported anxiety, depression, hostility and aggression, on the other hand, are associated with improved outcomes. During active phases of grief and crying, the immune system is more active; tears from crying contain toxins that are being released from the body, as compared with tears from cutting onions. Unexpressed grief takes a toll on the body and the psyche, festering within indefinitely until it is acknowledged and expressed. In my clinical work with people with cancer, sometimes the words of a Charlie Chaplin song run through my mind, “Smile though your heart is aching.”

I am surprised at how little we have learned in 31 years, as I hear commentaries remembering Jackie primarily for her “composure,” “dignity,” “grace” and “strength.” Many expressed profuse gratitude to her for comforting us as a nation by not crying. What if she had cried? Could that not have been a greater gift to our nation, to show a natural expression of grief? Why are we still so grateful to her for being so strong? This kind of strength is not valued by the body. We suffer greatly, in body and soul, from withholding our feelings from ourselves and from one another.

As for Jackie as a person and as a symbol, I wish that we could remember her more for her intelligence and her contributions to culture more than for her composure. Above all, I wish that Jackie’s greatest legacy to our generation had been permission to show feelings — for our sake more than for hers.

Author’s Addendum: In the years since I wrote in 1994 about our nation’s valuing Jackie Kennedy’s stoicism in the face of grief in 1963, our culture has evolved. We now actually valorize the expression of grief in popular culture.

In June, 2015 Sheryl Sandberg, the COO of Facebook and founder of Leanin.org, wrote about coping with extreme grief following her husband’s sudden death and appeared frequently in the media, raising much consciousness and cultural support for recognizing the experience of grief. This year saw the publication of her book co-written with psychologist Adam Grant entitled Option B: Facing Adversity, Building Resilience and Finding Joy, as well as a book by Lucy Hone, PhD, Resilient Grieving: Finding Strength and Embracing Life After a Loss that Changes Everything.

Recently, Prince Harry has come out about finally going into counseling after having shut down his emotions for two decades to avoid dealing with the death of his mother, Princess Diana. Prince Harry, Sheryl Sandberg and others recognize the need to educate the public and create a cultural environment that supports appropriate, healthy emotional expression.

And sadly, we have had too many national tragedies, school shootings, police shootings, terrorist attacks and so on that have provided opportunities for public expressions of grief and mourning.

However, while this cultural shift helps, it does not always filter down to individuals, families, and various subcultures in which the healthy expression of difficult emotions is not supported. Among those of us working in the field of psychoneuroimmunology, we have found that persons dealing with cancer who have not adequately expressed and processed grief are missing a vital – and perhaps crucial — aspect of healing.

At least our culture at large is embracing the expression of grief and mourning.

Join the conversation: Ask Holistic Cancer Coach Facebook Group

Diane Perlman, PhD, is a health coach and mediator practicing in Washington, DC, as well as a Certified Cancer Support Educator through BeatCancer.org, She is also a Visiting Scholar at the George Mason University School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution. She may be reached at 202- 775- 0777 or dianeperlman@gmail.com.